When Feelings Take Over Because There Is No Language

For many of us, the problem has never been that we feel too much. The problem is that we feel deeply, intensely, and often all at once, without having been given a way to translate those feelings into anything usable. When emotions arrive without language, they don’t move through us like they are supposed to do. They settle in and take root, making our inner landscape home. They blur the edges between what we are feeling and who we are. This is especially true with heavier emotions like anger, sadness, or fear. These feelings have weight. They demand attention. Without a learned way to express them, they can begin to consume our internal landscape. Instead of experiencing an emotion, we become merged with it. We stop saying, “I feel angry,” and start living as if, “I am angry.” The distinction may seem subtle, but psychologically and neurologically, it is enormous.

What often gets labeled as being “too emotional” is actually something much quieter and more structural: a lack of language. When there is no framework for naming what is happening inside us, the nervous system stays activated. The emotion has no outlet or completion. It simply loops. The longer it loops, the harder it becomes to step back and ask what the feeling is trying to communicate. This does not happen because people are incapable or unwilling to talk. It happens because many of us were never taught that emotions are meant to be translated.

For those of us raised by parents who believed that strong emotions were disruptive, manipulative, or something to be punished, expression was often shut down long before understanding could form. Phrases like “I’ll give you something to cry about,” or being sent away to “calm down” without guidance, taught us that feelings were problems to be contained, not messages to be understood. As children, we learned quickly that the safest option was silence. As adults, that silence often turns inward.

So when emotion shows up now, especially in moments of stress, conflict, or loss, we don’t instinctively reach for curiosity. We brace and try to endure…or, we drown. This is why so many people feel lost inside their emotions. Not because the emotions are wrong, but because there is nothing standing between the feeling and the self. Without language to act as a buffer between the two, emotion becomes identity. This is where emotional literacy begins, not by eliminating emotion, but by creating enough distance to listen to it.

Why Language Creates Space Instead of Suppression

For many people, the resistance to naming emotions comes from the idea that naming something means taking ownership of it. We are often taught that to name something is to claim responsibility for it. If you say, “I feel angry,” then you are expected to control it, justify it, or fix it. If you name sadness, you risk being told to explain it, minimize it, or move past it. So instead, many people learn a quieter strategy: don’t name it at all.

The belief goes something like this:

If I don’t label it, then it isn’t mine to deal with.

If I don’t put words to it, maybe it won’t count.

Maybe it won’t demand anything of me.

But this is where the logic breaks down.

When an emotion goes unnamed, it does not stop existing. Ignoring a problem has never made it disappear, and emotions are no different. Being unwilling or unable to label what we are feeling does not neutralize the emotion. It simply pushes it out of conscious awareness. What we are often doing instead is suppressing it. Many of us were taught this as a survival strategy. We learned early on that expressing emotion made things harder for the people around us, not easier. So we swallowed it and stayed quiet. We learned to be “fine” and, at least for a while, that may have worked. It kept the peace and reduced conflict. It made us more manageable and palatable. But suppression is not resolution and it’s not sustainable.

An emotion that is suppressed does not dissolve. It waits and builds through the body. We see it through reactivity to everything, exhaustion, anxiety, burnout, and it even manifests as physical symptoms like that upset stomach.

This is the cost of silence.

When we do not give an emotion language, we do not gain control over it. We lose the opportunity to understand it, respond to it, and care for it in a healthy way. The feeling remains present, but now it exists without context, without boundaries, and without support. Naming an emotion is not about making it bigger. It is about making it visible enough to work with. It is the difference between carrying something blindly and holding it in your hands, where you can actually see what it is asking for. Naming an emotion is not about blame or self-judgment. It is not a moral claim. It is a regulatory act. It creates a relationship between you and the feeling instead of allowing the feeling to take over the entire internal landscape.

Language does not mean, “This is who I am.” It means, “This is what is happening.” That distinction is what allows choice to return.

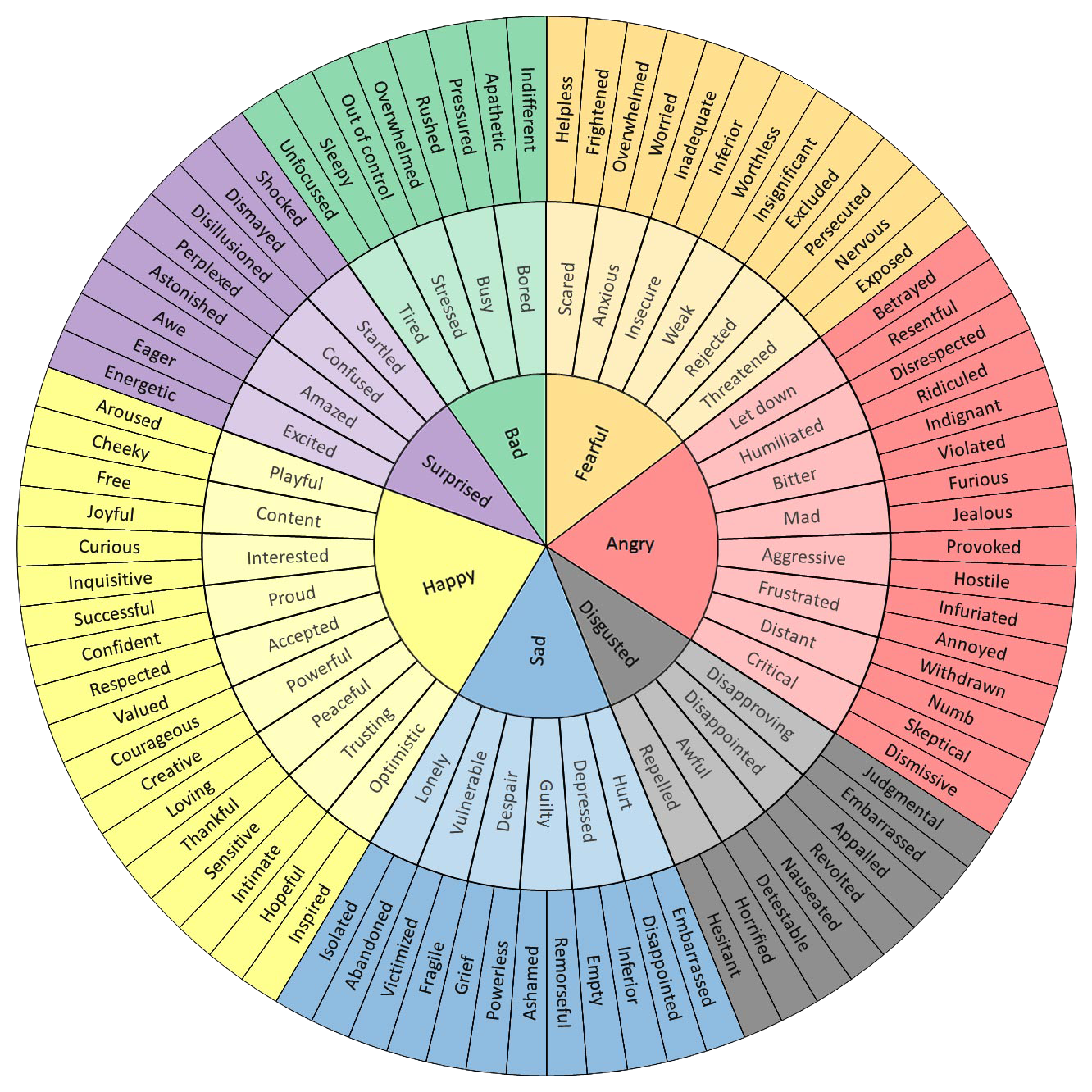

The Feelings Wheel

At first glance, the feelings wheel can look overwhelming. The outer edges are packed with descriptive words and adjectives we already use in everyday language when we talk about how we feel. These are often the words that come most naturally to us, because they are specific and situational. But as you move inward on the wheel, something important happens. Those specific descriptors begin to collapse into broader emotional categories. What looks like dozens of different feelings at the surface level eventually distills down into a much smaller set of core emotional states: surprised, bad, fearful, angry, disgusted, sad, and happy. This isn’t about oversimplifying human experience. It’s about recognizing patterns in how the nervous system communicates. What the wheel shows us is that many of the words we use to describe our inner experience are actually variations of the same underlying signal.

For example, you might notice yourself thinking, I feel disrespected. When you trace it inward on the wheel, you can see that disrespected falls under anger. That doesn’t mean you are “an angry person.” It simply means that something in your environment or in an interaction has crossed a boundary. Your body is responding to that violation by mobilizing energy. From there, a different kind of inquiry becomes possible.

Why do I feel angry right now?

What specifically feels disrespectful?

What value, limit, or need is being ignored here?

Instead of staying stuck in the intensity of the feeling, language allows you to move into meaning. Anger, in this case, may be calling you to set a clearer boundary or to advocate for yourself. It may be asking you to treat yourself with the respect that wasn’t offered to you in that moment.

If you find yourself feeling ashamed, the wheel helps you see that shame lives under sadness. Again, this doesn’t mean you are sad as a person. It means that something has touched a place of loss, disappointment, rejection, or unmet need. When shame is named this way, it becomes less paralyzing. You can begin asking different questions:

What expectation wasn’t met?

What story am I telling myself about this moment?

What would compassion look like here?

You might notice a moment where you feel confident. When you trace that word inward, you’ll see that confidence falls under happiness. It invites curiosity in a different direction.

What is happening right now that supports this feeling?

What environment, behavior, or choice contributed to this sense of confidence?

Those are moments worth paying attention to, because happiness isn’t just something to enjoy,it’s something to learn from.

This is why I encourage readers to actually spend time with the feelings wheel. Not as a diagnostic tool or a way to label yourself but as a reference point while you are learning the language of your emotional experience. When something comes up, you can sit with it and say, I’m feeling… and see where that word leads you. You can trace it inward, not to reduce it, but to understand it. Over time, this practice helps you step out of being overwhelmed by emotion and into a relationship with it.

I invite you to save this image, take a screenshot, or keep it somewhere accessible. Language is learned through repetition. The more often you practice identifying what you’re feeling and exploring what it might be asking for, the easier it becomes to respond intentionally rather than react automatically.

This is not about mastering emotions. It’s about listening to them long enough to hear what they’re trying to say. From there, the choice is yours on how you act on those emotions.

Every Emotion is Valid, It’s What We Do With It That Matters

This is where I come back to something I say often: every emotion is valid, but what we do with it is what matters. That sentence only works if choice exists. Choice only exists when we have language.

Take anger, for example. Anger is one of the easiest emotions to misdirect because it carries so much energy. When anger is unnamed, it tends to spill outward. It lashes out. It touches everything and everyone around us, often unintentionally. Words become sharp. Reactions become fast. Damage happens before we even realize what we’re responding to. Anger, in that state, feels explosive. But when anger is recognized something shifts. That same energy does not disappear, but it becomes usable. Anger can become motivational. It can energize us toward corrective action. It can clarify and protect our boundaries. It can point directly to what feels unjust, unsafe, or violated and clearly state, "this is not ok”. The difference is not the anger itself. The difference is whether it is unnamed and running the show, or named and being worked with.

Grief moves differently, but the pattern is similar. When grief goes unrecognized, it often collapses inward. It pulls us away from others. It isolates and draws us into dark, quiet spaces where everything feels heavy and lonely, and where connection feels almost impossible. Grief, left unnamed, can convince us that withdrawal is the only option. But when we can recognize sadness choice begins to reappear. We can still honor what is making us sad. We can still acknowledge the loss, the betrayal, and the ache of what is gone or what never was. But instead of disappearing into it, we can choose to connect. We can allow ourselves to be witnessed. We can bring our grief to the people we trust, rather than letting it seal us off from them. Naming grief does not diminish it. It makes it survivable.

Fear offers another example. Fear often keeps us frozen. It holds us back from experience. It keeps us in the same place, replaying the same patterns, because movement feels too risky. When fear remains unnamed, it often disguises itself as truth. I can’t. It’s not safe. This will end badly. But when we recognize fear as fear, rather than fact, it becomes an invitation to pause and evaluate. Is this situation actually the same as the one that taught me to be afraid? Or am I responding to an old script that no longer fits the present moment? Naming fear does not eliminate it, but it creates the possibility of bravery. It gives us the chance to respond instead of react.

Even the more diffuse states like burnout, stress, exhaustion, that general sense of feeling “bad” become more workable when we give them language. Without language, many of us default to extremes. We either keep pushing ourselves until we break, or we collapse inward and withdraw entirely. But when we can say, I’mf feeling burned out, overwhelmed, or exhausted, we can start asking what is causing it. What needs to be removed? What needs to change? What boundary has been crossed, ignored, or never set at all?

None of that is possible without language.

This is why naming matters so deeply. When emotions remain vague and unspoken, they tend to loom like monsters in a dark room that look shadowy, threatening, and unpredictable. They feel as though they could jump out at any moment and tear us apart. But when we turn the light on and say, this is what you are, something changes. The monster doesn’t vanish. It doesn’t suddenly become harmless. But it becomes knowable.

This is where I return to the monster metaphor I use so often. Once named, the monster is no longer a faceless terror peering at us from the corner. It becomes more approachable. Less threatening. Maybe it’s still prickly. Maybe its quills are up, like a porcupine protecting itself. But it is no longer unknowable. When something is no longer unknowable, it no longer has absolute power over us.

Language does not trap us inside our emotions. It frees us from being consumed by them. It allows us to step out of identification and into relationship. And from that place, choice becomes possible again.

Emotions Are Here To Help, Not Hurt

I want to close by coming back to something that often gets lost when we talk about emotions, especially the heavy ones: every emotion serves a purpose. Even the ones that feel bad and we wish would go away. Emotions are not design flaws or inconveniences. They are not signs that something is wrong with us, even when those feelings become chronic. They exist because, at a fundamental level, they help us survive, adapt, and respond to the world around us. Many of them are protective in nature. They are signals meant to interrupt autopilot and say, pay attention, something here matters.

There is a growing body of research, including work explored in Leonard Mlodinow’s book Emotional, that looks at emotions from an evolutionary perspective. I’m not going to unpack the science in depth here, because that’s not the point of this space. What matters is the core insight:

Emotions evolved because they help us improve the situations we are in.

They push us toward action when something is wrong, and they encourage us to continue behaviors that support connection, safety, and well-being when things are right.

Happiness reinforces what nourishes us. It tells us, this works so keep going. The heavier emotions do something different. Anger alerts us to injustice or violation. Fear tells us to pause and assess risk. Sadness and grief slow us down so we can process loss, change, or disconnection. Stress and exhaustion signal that something in our environment or expectations is unsustainable.

In other words, when an emotion shows up, especially an uncomfortable one, it’s often because whatever is happening is significant enough to deserve our attention. It’s an invitation to step back, reassess, and move into problem-solving rather than collapse, suppression, or reactivity. This is where language becomes so essential. When we can name what we’re feeling, we create space between the emotion and our response. That space is where choice lives. That’s where we stop being driven entirely by the feeling and start working with it instead. Not dismissing it. Not indulging it endlessly. But listening long enough to understand what it’s asking for. The takeaway here isn’t that we should try to feel less. It’s that we need better ways to relate to what we feel.

Emotions are not here to control us. They are here to inform us.

And when we give them language, we give ourselves the ability to respond with intention rather than impulse. That is where healing starts and agency returns. That is where emotions can finally do the job they were meant to do.

References

Al-Shawaf, Laith, et al. “Human Emotions: An Evolutionary Psychological Perspective.” Emotion Review, vol. 8, no. 2, 11 Feb. 2015, pp. 173–186, labs.la.utexas.edu/buss/files/2013/02/Al-ShawafEmotion-Review-2015.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914565518.

LeDoux, Joseph E. “Evolution of Human Emotion.” Evolution of the Primate Brain, vol. 195, 2012, pp. 431–442, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3600914/, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-53860-4.00021-0. Accessed 5 Feb. 2026.

Next Big Idea Club. “Why We Evolved to Feel Sad and Angry, according to Science.” Next Big Idea Club, 2022, nextbigideaclub.com/magazine/evolved-feel-sad-angry-according-science-podcast/33557/?srsltid=AfmBOooUhf4WZDABksDEHt95Hyk9b0LKnMVM1myEUZQiOLhyfCsqbE5y. Accessed 5 Feb. 2026.